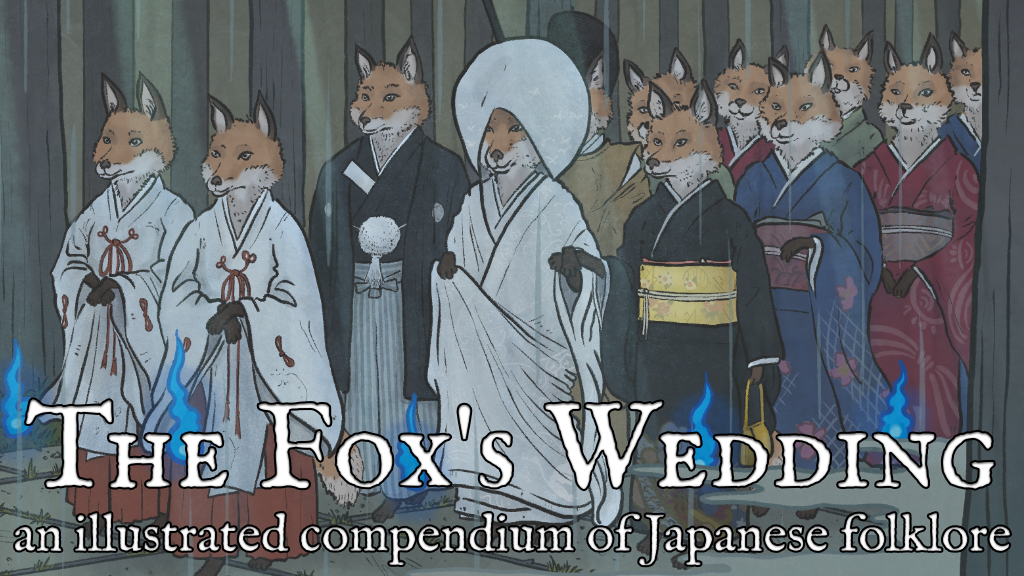

Byakko, the white fox

about 4 years ago

– Fri, Dec 04, 2020 at 11:59:57 PM

Greetings yokai fans!

We just passed 1000% funding! What a milestone!

Today I'd like to share a little "behind the scenes" work and talk about some of the kitsune folklore you'll see in the book. Keep in mind that since this is folklore and not mythology, there are many different ways of categorizing kitsune, many of which contradict each other.

Byakko (白狐) literally means "white fox." They are one of the five "families" of kitsune. Kitsune are born as the ordinary red foxes you think of when you imagine a fox. As they grow, some of them transform into the various colors of foxes you'll see in folklore; white, black, gold, and silver. Think of it sort of like Hogwarts houses. No color fox is necessarily higher or lower than the others. They just have different features. And, not all kitsune "level up" in this way; some remain red foxes and "free agents" their whole lives.

Byakko are the foxes most closely associated with Shinto and the god Inari. Not every Shinto-associated fox is a byakko, but every byakko is a servant of Inari. As a byakko spends its life serving its god, it will rank up further, achieving various honors and degrees from the shrines it serves. Sort of like boy scout badges. And, as they age, they can also increase in power and evolve into higher forms of kitsune, shedding their bodies and becoming entirely spiritual entities. One of the requirements that byakko must fulfill as they rank up is that they do not possess humans or play tricks on them, aside from perhaps teaching them a minor lesson here and there. Byakko are not evil.

A number of the foxes you'll see in the book are byakko. And some of the foxes in my previous books are also byakko, a famous example being Kuzunoha, the mother of Abe no Seimei.

Creating an Illustration

When I create an entry for the book, I start with pulling information from as many sources as possible. Then I translate, and break apart the information into what I find most interesting and compelling. I distill it down to its major points, including a description, a history, and if possible a few good examples from legends. Then I start brainstorming thumbnails and come up with the image I want to make to go along with the writeup.

I start with rough pencil sketches to create a composition I like. This is actually one of the most important steps, because it acts as the foundation for the entire image. Sometimes it takes many different sketches to come up with the one I'm going to use, but it's worth taking as much time as necessary at this stage. Every extra minute spent on sketching and designing saves an hour down the road. After I choose a sketch I like, I can generally see the finished product in my head.

The next step is to scan it and put in into my computer. Then I digitally ink the piece. It's more than just tracing lines. The lines have to feel organic and capture the energy of the piece, which can be challenging when you're drawing on top of a sketch. The same line will look slightly different if it's drawn slowly or quickly, and it will subtly affect the final piece. So this stage requires focus and attention.

After inking, it becomes easy to tell if there are any problems you've overlooked in the sketch. If it looks unbalanced or incomplete in a black and white line drawing, then it will look even worse when painted. So at this step it's important to make sure I'm fully happy with the direction it's taking. In worse case scenarios, I'll scrap it and start over (that usually means that I didn't spend enough time on the sketch). In this case, it felt lonely. So I added a bunch of little kitsune statues like the ones you can see in the Kickstarter video.

Happy with the inking, it's time to move on to painting. If I did everything properly up until now, painting tends to be a breeze. I'll sometimes zone out for a whole day while painting, forgetting to eat or even go to the bathroom, and when I finally break out of that zone I'm sitting in front of a finished piece, feeling very hungry.

When painting digitally it helps to use a limited palette. I use a palette based on the traditional colors of Japan, which would have been the colors available to traditional woodblock print makers over a hundred years ago. I paint by blocking in major sections of similar colors, and then working my way up from layer to layer, just as a woodblock printers do. Since it's digital, I manually add textures which would have been naturally formed by the meeting of paper and wood grains in traditional formats. I also apply a little bit of rough texture to simulate aging. I'm not trying to exactly copy the style of woodblock prints, but it's where much of my inspiration comes from, so I want to pay homage to them in my own style.

And that's how we get from old Japanese text to modern illustration!